July 28, 2021

This analysis complements the journalism stories of Red Flags or Resilience? and offers policy recommendations for bolstering the resilience of vulnerable populations in Malaysia.

Fifteen-year-old Rhan* was growing up in the cocoon of his family, living in a communal longhouse-hut, tending to animals, foraging the jungle for edible plants and picking wood for cooking and warmth. Living in a southeastern province in Myanmar (then known as Burma), he attended school and spent evenings listening to chats on military incursions and threats that ethnic groups faced in the country. In 1988, a military attack caused Rhan and many youths to flee to the jungles. At the campsite, Rhan worked in the kitchen and coordinated the meals. But soon they had to make a choice—fight or flight. Rhan chose to flee.

With 25 others, he embarked on a journey by road and river to reach a northwestern state, Penang, in Malaysia (see map) where they were dropped off by a smuggler. Rhan struggled to establish a secure life in Malaysia, initially sleeping under plastic sheets in the jungle near where he worked illegally as a construction worker.

Thirty years on, Rhan, now almost 50, is still a refugee, but he possesses an identity in the form of a refugee card from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). He leads his community of Burmese refugees and asylum seekers in its events, seeks jobs for people, runs the community school, manages the food bank, distributes food, offers counseling to those in distress, orients newcomers to the local area, and builds up his knowledge on COVID-19 and immigration laws. Despite his progress and sense of community in Malaysia, for Rhan, a question remains: was fleeing Myanmar worth it when compared to the endless wait to resettle or become a citizen in Malaysia? Like almost every refugee, asylum seeker, and stateless person, Rhan sees no solutions beyond faraway dreams.

Further, the little sense of security Rhan established by having a job, food on the table, education for his children, and small savings came apart as COVID-19 raged without discrimination, infecting people and deepening the disenfranchisement of vulnerable populations. The health and safety of those with no identity cards or status were not prioritized. They fell below citizens, expatriates, foreign retirees, documented migrant workers, and students on visas in the pandemic containment and prevention mechanisms, causing infections to spread among undocumented communities living in crowded and cramped housing areas and leading many to be crudely detained and deported.

Rhan is one of the 178,920 refugees and asylum seekers registered with UNHCR in Malaysia as of the end of March 2021. His experiences are not vastly different from those of new refugees or asylum seekers, whose number peaked in 2013 when 28,434 refugees arrived in Malaysia. Newer arrivals today have more-established support networks compared to 30 years ago. Most—about 85 percent—of the refugees or asylum seekers are from Myanmar’s diverse ethnic groups, and the rest are from 50 other countries. More than two-thirds are men, and a quarter are children younger than 14. Malaysia, unlike 143 other countries, is not a signatory to the 1951 Convention on Refugees and International Law, 2020. There are also unverifiable numbers of stateless people, with figures ranging from 10,000 to 50,000, living in the country, mainly in the state of Sabah in East Malaysia. They face limited access to legal employment, education, health care, and other public services, as many have irregular or no documentation.

CREDIT: Adobe Stock/Reuters/Lim Huey Teng

This undocumented community lives in a constellation of many people—2 million documented workers, an estimated up to 4 million undocumented migrant workers, and a citizen population of 29.7 million. The citizen population is diverse: 69.6 percent are bumiputras (“sons of the soil”), who are Malay-Muslims and natives of Sabah and Sarawak; 22.6 percent are Chinese; 6.8 percent are Indians; and 1 percent are categorized as “Other.” Malaysia’s national bumiputra policy, as stipulated in the country’s Constitution (Article 153), privileges Malays who are predominantly Muslims, despite the country’s heterogeneity. Non-Muslim citizens live and adapt to the discrimination they face through the bumiputra policies. Many refugees and asylum seekers are also Muslims, but the community of non-Muslim refugees, asylum seekers, and stateless people, faces a deeper displacement and learns from non-Muslim citizens how to practice their religion and to respectfully observe multicultural and multireligious practices.

Refugees and asylum seekers already struggle to meet their basic needs, but they also face legal and administrative hurdles. Like Rhan, many wish to pick up skills, be educated, become employable and independent. Rhan is trilingual, speaking, reading, and writing in Malay, English, and the native tongue of his ethnic group. But he struggles to gain a foothold in the main employment market, as he is invisible as a refugee. Even before COVID-19, the quality of services given to refugees and asylum seekers was fragmented, simply because they are seen as outsiders. Rhan wishes he could have been given more opportunities to serve and contribute to Malaysia, as he is grateful for the 30 years he has lived there. If the system were different, Rhan could have worked legally in Malaysia’s industries, helping the country and himself—a win for each. But it was not to be.

The pandemic has increased the fragility of the status of refugees, asylum seekers, and stateless people. They are disproportionately impacted by COVID-19 and the attendant prevention and containment measures. They face inadequate access to information in their own languages and disruptions in welfare and health services, succumb to continuous raids, and fear being detained, deported, and COVID infected. Many have lost jobs, which means less money for basic necessities.

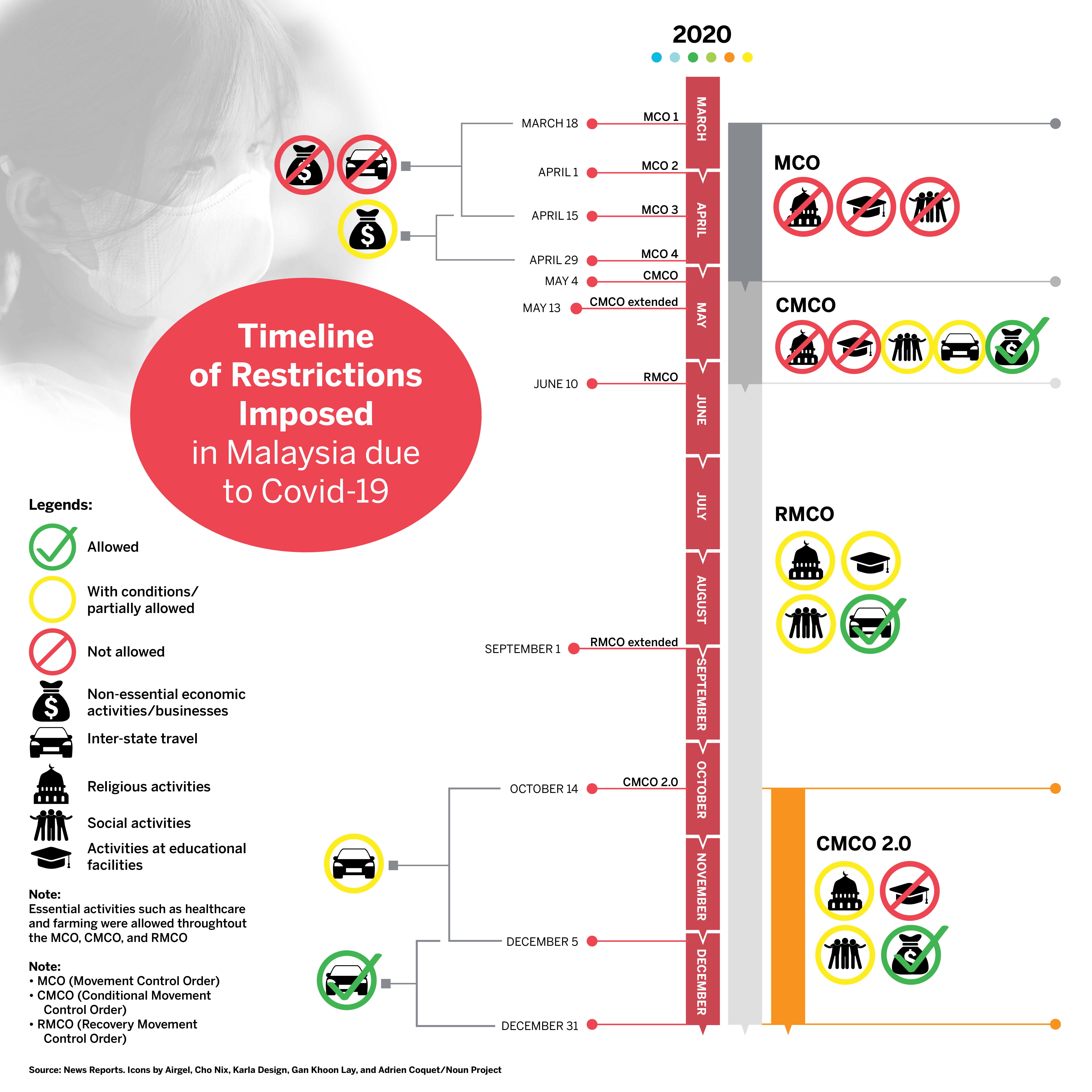

Since Malaysia’s first confirmed positive COVID-19 case on January 25, 2020, cases increased rapidly, reaching nearly 470,100 cases with 1,902 deaths by May 17, 2021. The key containment effort is a national lockdown, called Movement Control Order (MCO), with various restrictions. Table 1 is an infographic that shows the restriction implemented over the first three waves of COVID-19 infections.

During the first three-month MCO, which began May 18, 2020, the government started COVID testing undocumented migrants living in urban areas as a means to contain the spread of the virus. To persuade them to be tested, the government said it would not arrest and detain people with no documentation. Yet on May 1, 2020, hundreds of undocumented migrant workers, refugees, and children were arrested during a COVID-test exercise that was also an immigration raid. Subsequent raids in various locations saw more arrests. On May 12, the government announced it needed to deport undocumented people back to their countries of origin to contain COVID-19 and stop the trafficking of people into Malaysia. In this swoop, refugees and asylum seekers without valid UNHCR identity cards also faced detentions and deportations back to countries they had fled from. The government had reneged on its promise, and COVID testing was used to target its millions of undocumented people. Deportation data showed that 400 individuals from 11 detention centers were sent back to Myanmar, with some testing positive for COVID-19 upon arrival. An additional 3,000 were scheduled to be deported to Myanmar in June 2020, though whether that occurred remains unverifiable, as there is no updated information.

CREDIT: Adobe Stock/Reuters/Lim Huey Teng

Among detainees, 2,000 people were infected with COVID-19 in the camps, where people, including women and children, lived in unsanitary conditions. Some ran away to hide in the jungles. Initially, the government even wanted to charge undocumented people $10 for each COVID screening. These screenings became immigration exercises to “weed out illegals,” an action defended by Senior Minister Datuk Seri Ismail Sabri Yaakob. Nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) such as Tenaganita, Refuge for Refugees, and Suhakam (Human Rights Commission of Malaysia) issued statements on the inhuman nature of arrests and detentions, which were detrimental to the health and safety of the refugees.

This weeding-out effort, contrary to Malaysia’s earlier receptive approach toward refugees and asylum seekers, climaxed when the country also refused the disembarkation of refugees at sea. Two boatloads of Rohingyas were escorted out of territorial waters, against the international humanitarian norm of first letting people disembark to receive food, water, and blankets. It highlighted how COVID-19 had shifted Malaysia’s compassionate and humanitarian efforts toward refugees and asylum seekers to sterner immigration-based actions of deportations. Yet it startled when, in 2021, Malaysia loaded three Myanmar navy boats with more than 1,000 refugees and asylum seekers for them to be returned to Myanmar, disregarding the military takeover in the February 1 coup that deposed the elected government. Some among these deportees were from ethnic groups that were already at odds with the military.

There were strong criticisms from international, regional, and national NGOs, as this was a violation of the deportees’ security and safety. In response to the judicial reviews filed by Amnesty International and Asylum Access, an interim stay order was issued by Malaysia’s High Court. The Malaysian director general of immigration’s response was to insist that people left voluntarily, of “their own free will, without being forced.” Even as deportations were taking place in 2020, ethnic groups appealed to UNHCR for intervention and protection. But UNHCR Malaysia is strapped. Its representatives have been unable to visit any detainees since 2019—before the COVID onset—as the government has not given visitation rights to detention camps for the UN body or for national refugee-focused NGOs. The deportation acts are also against the principle of nonrefoulement in international law, which protects individuals from being returned to a country where they may be exposed to threat of serious harm, including threats from a third country, and also ensures individuals are being sent to a third country that is willing and able to provide protection.

To date, there is little news on the safety or welfare of the navy-ship deportees. Instead of showing support for vulnerable populations, the Malaysian government made its stand clear against certain groups: Home Minister Datuk Seri Hamzah Zainudin said Rohingyas have “no status, rights or basis to state demands from the Malaysian government…which does not recognise their status as refugees…but as illegal immigrants holding UNHCR cards.” Incidentally, a Malaysian reporter who wrote on the arrests of refugees and asylum seekers in the pandemic and on the government actions was charged with breaching the peace. And in very recent raids, undocumented people, though they faced no threats of arrests, were sprayed with disinfectants—a health hazard—as a means to vaccinate the community.

CREDIT: Adobe Stock/Reuters/Lim Huey Teng

Citizens also face COVID stresses with job losses and financial difficulties. Resentment against refugees and asylum seekers has built up. Some Malaysians felt jobs were going to them as they worked for low wages. There was also a fear that as refugees and asylum seekers lived in crowded and squalid places, they could be COVID-19 spreaders to Malaysians. There was support for the raids and deportations of undocumented people. Degrading and belittling comments grew voluminously on social media. One instance shows how rapidly hate built up against refugee leader and activist Zafar Ahmad Abdul Ghani, of the Myanmar Ethnic Rohingya Human Rights Organisation Malaysia, who was targeted and misinformation spread that he had dared to ask for Malaysian citizenship. Even now, a year later, he receives online abuse, has not stepped out of his home, and is depressed over the hate. Furthermore, his residency status has remained in limbo, and his Malaysian wife has stopped sending their children to school over this backlash. In another incident, the Malaysian ambassador for the European Rohingya Council, Tengku Emma Zuriana Tengku Azmi, was threatened with sexual assaults and faced a virulent sharing of online hatred (18,000 shares) because she had asked for a reversal of the government’s push-back-to-sea policy on boatloads of Rohingya refugees. Voices of activists who spoke up for the rights of refugees and asylum seekers were censored or silenced by authorities.

CREDIT: Adobe Stock/Reuters/Lim Huey Teng

The COVID-19 containment and prevention mechanisms sent a clear message: undocumented communities of refugees, asylum seekers, and stateless people, and migrant workers without valid passes were not welcome, had overstayed, and Malaysia no longer wanted to remain hospitable to its guests.

COVID-19 has caused deaths, taken a toll on frontline workers in essential services, fissured the economy, and left more people living in poverty. The pandemic, a major health threat, has disproportionally impacted vulnerable populations like refugees, asylum seekers, and stateless people who deal with a triple whammy of unmet basic needs, lack of adequate COVID-19 prevention, and possible deportation. There is a need to improve systems, processes, and policies for the betterment, safety, and security of all people. This pandemic’s impact on vulnerable groups must be discussed and measures reviewed. Here are some recommendations:

Rhan cannot stop thinking. Reflecting, he says:

CREDIT: Adobe Stock/Reuters/Lim Huey Teng

“We still want to go back. We love our motherland. But we have to live in another land for now. How long more—no one knows. Right now, more trouble with the military in power. It is worse now. How to go back? How to stay on? We escaped to save ourselves. We can take care of people in our community. But our vulnerability is always there, and in this pandemic, we have been pushed out even further. But we continue, as that is all that we can do.”

His life came apart before. He still fears losing his culture, religion, and identity, and knows he might die, stateless, in Malaysia.

Refuge remains a minefield.

* Names marked with an asterisk have been changed to protect people’s identity and safety.

Braema Mathiaparanam is an independent researcher who is also a Visiting Senior Research Fellow at Penang Institute in Malaysia. She is a former journalist, a founder-member of organizations for human rights and migrant workers, and is currently focusing on conflict studies.

COVID-19’s Impact on Atrocity Risks