March 25, 2021

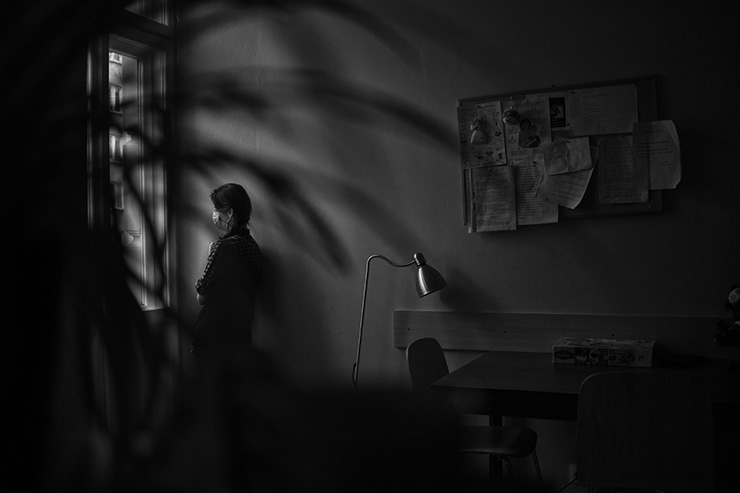

One Friday night at the end of October 2020, Krysia Paszko, then a 17-year-old high school student, gathered with a crowd of 100,000 people on Warsaw streets to protest a decision by the constitutional court to ban most abortions. Despite tightening restrictions in response to the coronavirus, the demonstration marked one of the largest in Poland’s history since the fall of communism, a show of anger against the ruling right-wing Law and Justice Party. As things wound down, Paszko headed home and tried to sleep. When 2 AM rolled around and Paszko was still awake, she opened a Facebook page she’d created to help domestic violence survivors, and a message popped up.

CREDIT: Maciek Nabrdalik / VII for Stanley Center

“Help. Please help,” it said. “He wants me to leave the flat. I have blood on my face. I don’t know where to go. What should I do?” Paszko proceeded to ask a few questions. The woman explained that her partner had gone out to a friend’s party and came home drunk. He packed her things in a suitcase and told her that she should be ready for more violence if she called the police. Paszko, in the meantime, was coordinating with shelters in the area to secure a spot for the woman. Within a few hours, the woman made it out safely to a crisis-intervention center.

In early April, roughly a month after Poland went into its first lockdown to stem the spread of the coronavirus, Paszko was watching a report on TV about Europe’s surge in domestic-violence cases. She learned that France had implemented a program using a code word, “Mask 19,” that women could use in pharmacies to escape situations of domestic violence during lockdown. Discovering that Centrum Praw Kobiet (CPK), the largest women’s rights center in Poland that provides shelter and other services to domestic-violence survivors, reported a 50 percent increase in calls received by its domestic-violence hotline in March, Paszko had an idea.

Paszko took to her private Facebook page, where she posted a message. “If you are in quarantine or isolation with a toxic or violent person,” she wrote in Polish, “send a message to this fictitious cosmetics page,” to which she linked. If you ask a question about natural cosmetics,” Paszko explained, “we will monitor you; if you write ‘STOP,’ we will call the police on your behalf. Paszko couldn’t keep track of the flood of messages and requests she received. Within days, she partnered with CPK, and the post has since been shared thousands of times.

CREDIT: Maciek Nabrdalik / VII for Stanley Center

Around the clock, volunteers like Paszko, as well as psychologists and private attorneys, attend to messages. The page is so convincing that it sometimes receives requests for information about the advertised natural cosmetics. To protect women whose partners monitor their communications, the team developed a system of coded questions to determine the type of assistance needed. For instance, “What kind of skin problems do you have?” “Do other family members suffer from the same condition?” “When did the skin problem start?”

Since spring 2020, upward of 500 women throughout Poland, and Polish women living in Holland and Germany, have received help through the Facebook page. According to Monika Perdjon, a therapist and emergency responder with CPK, requests for assistance increased in the fall after Poland restricted people’s movement to curb the second wave of the virus.

Last spring, the United Nations warned that with lockdown measures and other restrictions, women and girls were trapped at home with their abusers, leading to what it called a “shadow pandemic.” Emergency calls for domestic-violence cases surged across the world. Before the pandemic, though, the scale of domestic violence had long been hidden in Poland. The ultraconservative Law and Justice Party has attempted to downplay—or possibly cover up—the extent to which gender inequality and violence are entrenched in Polish society. In August, a 2019 study commissioned by the government but not made public was leaked to the press. It found that 63 percent of Polish women had experienced some form of domestic violence in their lives. The study noted that what connects perpetrators is that they enjoy a sense of impunity—“they feel unpunished.”

CREDIT: Maciek Nabrdalik / VII for Stanley Center

The leaked study came on the heels of reports that, in July, Polish Justice Minister Zbigniew Ziobro filed a request with the Ministry for Family, Work, and Social Policy to withdraw Poland from the Istanbul Convention, a Council of Europe treaty created to combat violence against women and domestic violence. Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki then asked the country’s constitutional court, widely considered to be controlled by the Law and Justice Party, to determine whether the convention contradicts the Polish constitution. Morawiecki and other conservatives claim the treaty represents an ideological view on gender at odds with Poland’s traditional family values. News outlets reported that Poland aims instead to create a regional treaty with other Central and Eastern European countries on “family rights.”

This so-called war on the notion of “gender” is backed both by members of the ruling party and the Catholic Church and increasingly co-opted by right-wing activists. Ordo Iuris, an ultraconservative group, led efforts to replace the Istanbul Convention. According to Karolina Pawlowska, director of the international law center at Ordo Iuris, the treaty adopts the leftist, radical neomarxist ideology of gender being socially constructed. “It’s a document that perceives violence against women only in terms of this gender perspective—as something that is not caused by pathologies like alcoholism, pornography, family problems, but that arise from a structure of society,” Pawlowska told me.

Efforts to withdraw from the convention and a court decision in October to ban most abortions—which sparked nationwide protests that continued through December—represent “a very consistent march towards limiting women’s rights in Poland,” Zuzanna Warso, an expert in human rights with the Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights, said. Poland already has one of Europe’s most restrictive abortion laws. Still, the ruling party has repeatedly attempted to curb sexual and reproductive rights. An open letter signed by dozens of organizations in November 2020 highlighted a few such attempts: “hate speech and policies that promote intolerance and discrimination against LGBTI+ people and undermine their rights, including the establishment of so-called ‘LGBTI-free zones’ in numerous municipalities across the country; as well as the continued erosion of judicial independence and other fundamental rights and rule of law principles in Poland.” According to Warso, Poland’s signing and ratifying the convention culminated from years of advocacy, and its withdrawal would be a “huge loss” for civil society and the women’s rights movement.

CREDIT: Maciek Nabrdalik / VII for Stanley Center

Still, the pandemic may have been used as a pretext to further scale back legal protections for women in Poland. One theory for the timing of these efforts, explained Warso, is that the ruling party and conservative groups “hoped that people would not go into the streets in such huge numbers for fear of the virus.” If protests did occur, Warso further explained, protestors could be blamed for higher rates of infection.

In an analysis of COVID-19 and atrocity crime prevention, the Asia-Pacific Centre for the Responsibility to Protect noted that gender inequality is closely intertwined with conflict and atrocity crime. The greater the gender inequality, the higher the risk of atrocity crime, including gender-based crimes. Of particular concern, it noted, is the increase in domestic violence, evidenced in countries worldwide. “The risk of widespread and systematic sexual and gender-based violence is significantly higher in states with weak or no laws relating to intimate partner/domestic violence and where sociocultural norms are more permissive of this violence,” Dr. Sarah Teitt, deputy director of the center, wrote.

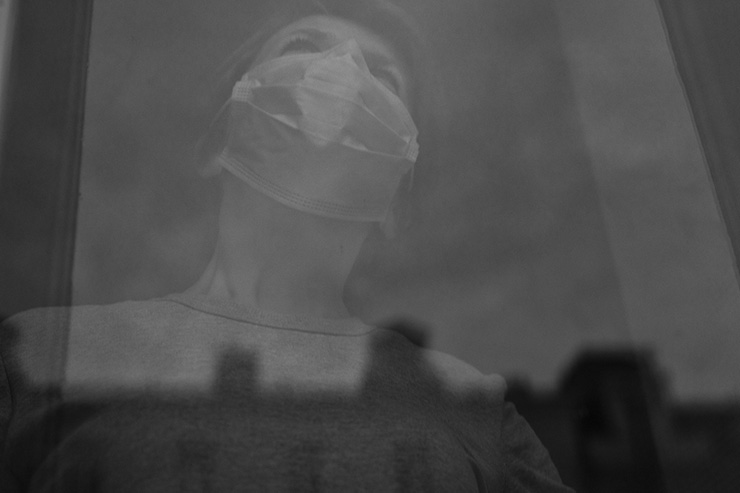

In Poland, CPK, the women’s rights center, found that violence both escalated in preexisting contexts and began in relationships for the first time after the spring lockdown. CPK found, anecdotally, that far more women were requesting space in its shelter but fewer were coming—women had concerns about the spread of the virus or were under surveillance by their partner and unable to slip out.

CPK’s shelter takes up one floor of a typical building in the center of Warsaw, among trendy shops and cafes. The space, whose location is hidden from the public, can house up to 20 women and their children, including those who sought help through the Facebook cosmetics page or were referred from other crisis centers.

Kasia, 30, and her mother, Silwia, 50, arrived at the shelter in November after spending a few months in an emergency center. For 32 years, Silwia explained, she’d endured crippling domestic violence at the hands of her husband. He was physically, sexually, and emotionally abusive. Kasia, who lived with her parents and two siblings until fleeing, had spent her life in a shadow, attempting to make herself invisible and small to avoid her father’s violent outbursts, especially after he’d been drinking. But mostly, the man directed his attention on Silwia. Sometimes the family called the police, but even after filing several reports, nothing changed.

CREDIT: Maciek Nabrdalik / VII for Stanley Center

Over the years, Silwia made several attempts to escape her husband. More than a dozen times, she left. Every time he would find her, drop to his knees, and beg her to come home, promising that things would be different. Silwia, having little contact with the outside world, didn’t fully comprehend that such manipulation techniques were part of a pattern of behavior in domestic-violence situations. She simply thought she’d married a bad man and had been unlucky. But about a year ago, when her husband broke her phone, he bought her a smartphone with internet. When he left for work and wasn’t controlling her cell-phone usage, Silwia started reading up on domestic violence and cycles of abuse. “Everything started to make sense,” she said.

When spring came and the pandemic hit, Silwia’s husband met a woman he said he’d like to invite over for dinner. “It’s a pandemic—we’re not supposed to invite anyone,” Silwia told him. “He was saying, ‘Oh, get over the virus, do you really believe it exists?’” He invited the woman anyway. Then he proposed that the family rent a room out to her. Silwia protested. Later that night, around 11, Silwia pretended to be asleep in her bedroom when her husband burst in drunk, hurling insults. Silwia remembers thinking, “This is it. I can’t be with this man anymore.”

CREDIT: Maciek Nabrdalik / VII for Stanley Center

Kasia heard her mother scream for help. She bolted upstairs and broke her mother free of her father’s grip. They ran to her room and locked the door, but the man broke through. At some point, one of Kasia’s siblings came home and called the police. The police arrived but left soon after, despite Silwia’s pleas. “Those police visits would often escalate the argument,” Kasia said. “The police did nothing for 30 years…he was protected all his life.”

CREDIT: Maciek Nabrdalik / VII for Stanley Center

The next morning, Kasia and her mother fled, first to an emergency shelter and then to CPK. Silwia has since filed for divorce, and she and Kasia have begun to process the trauma. “Since I ran away, I feel a hope growing inside of me that we will survive, that this is the beginning of a new chapter and a new life,” Kasia said.

But while Silwia has freed herself of her husband’s fetters, she worries for the women who will come after her. “For men like him, the pandemic is not a problem.” Having witnessed repeated violence against her mother long before the pandemic, Kasia agreed. “The Polish government is trying to hide the fact that there is such a big issue of domestic violence,” she said. “Domestic violence is real and is happening and people are not protected.”

All images by Maciek Nabrdalik / VII for Stanley Center.

A version of this article was originally published in The Guardian.

Annie Hylton discusses her reporting about gender-based violence in Poland on the Global Dispatches Podcast with Mark Leon Goldberg (May 3, 2021). Listen to the episode:

Annie Hylton is a writer and investigative journalist from Canada, based in Paris. She is a non-practicing lawyer with a background in international humanitarian law and human rights. She reports on gender, migration, and human rights and teaches at Sciences Po-Paris.

Maciek Nabrdalik is a Warsaw-based documentary photographer whose primary focus is on sociological changes in Eastern Europe. His work has been published and exhibited internationally and has been honored with awards from World Press Photo, Pictures of the Year International, and NPPA’s The Best of Photojournalism. He is the author of three books and has been a member of the VII Photo Agency since 2010. www.nabrdalik.com

COVID-19’s Impact on Atrocity Risks